Alles über chinesische Grammatik

Before we talk all about Chinese grammar, we’d better reach an agreement: learning Chinese grammar is crucial to learning the Mandarin language. Even though this sounds obvious, many Chinese learners approach learning Chinese as learning vocabulary only. This is not the right approach to fluency.

Let’s also make clear what ‘grammar’ really means, so let’s check the definition of it first:

- In linguistics, grammar (from Ancient Greek γραμματική) is the set of structural rules governing the composition of clauses, phrases, and words in a natural language. (from Wikipedia)

As you can see from the definition, if you do not learn grammar, you can not go further when you learn a foreign language, especially a new language like Chinese — which is quite different from your mother tongue.

There is an idiom from Sun Tzu’s Art of War: “Know yourself and know your enemy, and you will never be defeated.” If we take Chinese learning as a war, before we know ‘how’ to defeat grammar, we should know ‘what’ Chinese grammar is like.

Here are some tips for improving your Chinese grammar, based on its features.

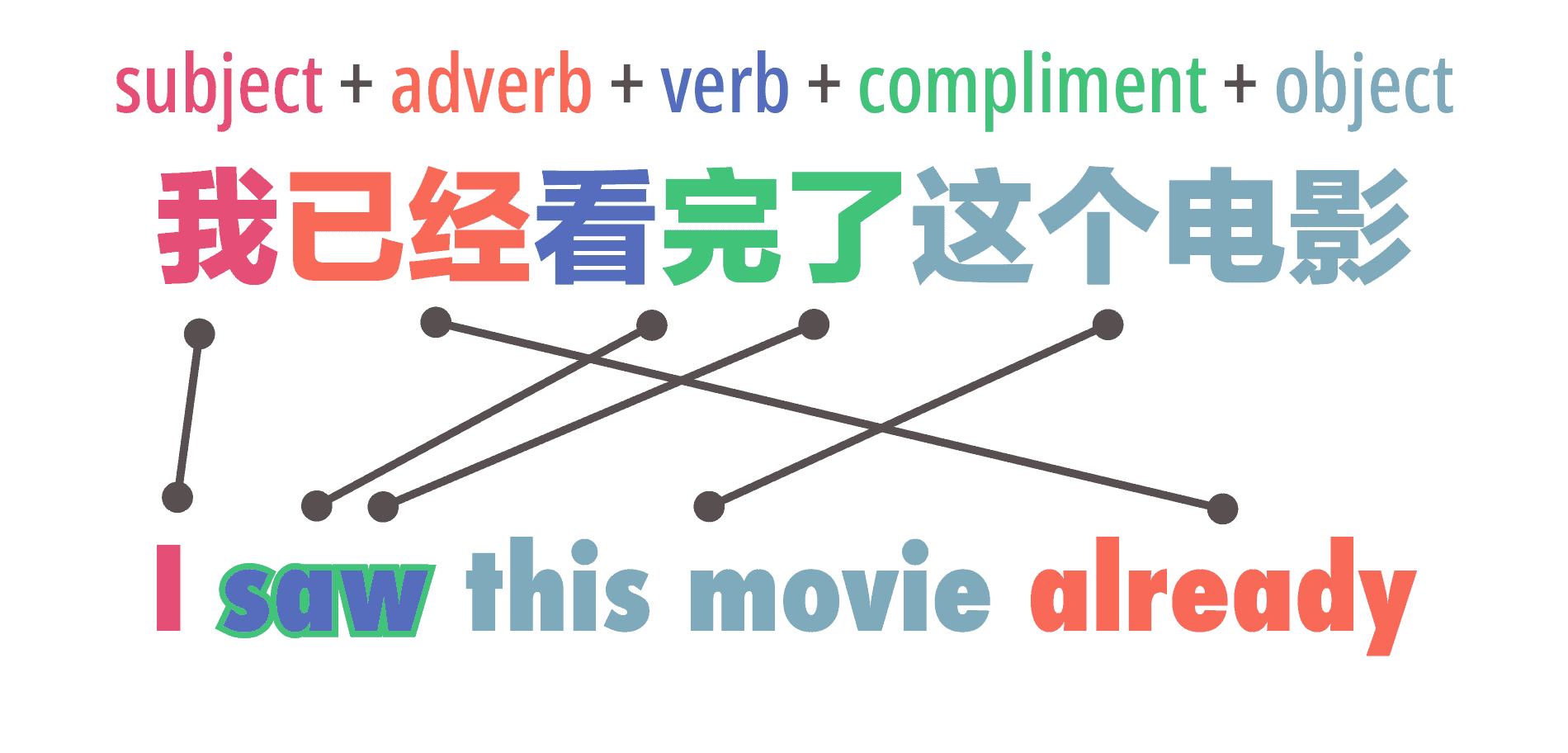

Chinese word order

The similarity of word order in your mother tongue and foreign language can determine the difficulty of learning the foreign language, especially at the beginning.

It can be good news to learners who can speak English because word order in Chinese is very similar to that of English. Even though there are similar characters in Japanese as in Chinese, learning Chinese grammar is not so easy for Japanese speakers as for English speakers.

Read in more detail about Chinese word order & sentence structure here.

Keep the sentence structure ‘SVO’ in mind

Despite how long you have been learning Chinese, you should remember that more than 90% of the declarative sentences develop on the basic structure as ‘SVO’.

‘SVO’ stands for ‘Subject-Verb-Object’, which can be equivalent to ‘Someone Do Something’ or ‘Someone/something Be What-to-be-like’.

For example, you must see the following sentences at the beginning level:

- 她是Alice。(She is Alice.)

- 她说汉语。(She speaks Chinese.)

- 她很聪明。(She is clever.)

When your level goes up, you may find most complex sentences follow the basic structure as well.

For example:

- 那个叫Alice的聪明女孩说了很多有意思的汉语。

(That smart girl named Alice spoke a lot of interesting Chinese.)

It is a long sentence, but we just add some modifications to each part of the basic structure.

If you try to divide the sentence into SVO parts, you can find:

- 那个叫Alice的聪明女孩 = Subject

- 说(了) = Verb

- 很多有意思的汉语 = Object

You can open any Chinese book at your hand or click any Chinese article online, select a paragraph, try to figure out the structure of the sentences. You may find most of them follow or develop from the basic SVO structure.

‘When’ and ‘where’ always come first than ‘what you do’

Chinese prefer to tell time and location first. The common order of making a sentence with time and location information is:

S. + time word + location phrase + V.O.

It can be seen as ‘someone some time at some place doing something’.

For example:

- 我昨天在家学汉语。(I studied Chinese at home yesterday.)

- 我明天去饭店吃饭。(I will go eat at the restaurant tomorrow.)

There is a Chinese joke which says ‘the most important always comes the last’, and it indicates Chinese prefer defining the range of time and location first and providing key information at the end to make an emphasis.

It is quite different from how you make sentences in English. So you need to consciously remind yourself: tell ‘when’ and ‘where’ first!

Modifiers are always put before nouns

If you want to provide details related to someone or something, you should tell the detailed features first.

For example, if you want to introduce a new friend you met at an event yesterday, you should say:

- 他/她是我昨天在活动认识的朋友。(He/she is a friend I met at an event yesterday.)

Or if you want to spot your friend by describing his or her clothing and appearance, you should say:

- 那个穿黑衣服的、又高又瘦的人是我朋友。(The person who is tall and thin in black is my friend.)

Although you do not need to make long sentences as the examples above when you are at the elementary level, you should be aware that you should tell listeners ‘how’ someone or something is like and then tell them ‘who’ or ‘what’ it is.

This feature can help you grasp the general meaning of a sentence quickly. If you are reading a long sentence where you are unable to define the basic structure to understand the meaning, a good way to get out of the trouble is to find central words and modifiers.

Some tips for recognizing modifiers and central words during comprehensive reading: highlight all the ‘的’.

Just keep it in mind: any word that follows ‘的’ is a noun that can be seen as a central word, and no matter how long is the phrase before ‘的’, is a modifier.

Take the first sentences above as an example:

- 他/她是我昨天在活动认识的朋友。

Here ‘朋友’ is the central word and ‘我昨天在活动认识’ is the modifier.

Then, cover or delete the modifier, you can easily figure out the fundamental meaning of the sentence is ‘他/她 是 朋友 (He/she is (a) friend)’.

Do-and-don’t of changing word order

First, remember that you do not need to change word order when asking questions. There are many particles that work for questioning in Chinese to indicate interrogative meaning.

For example, when you make a statement as ‘她是Alice (She is Alice)’, the questions can be ‘她是Alice吗 (Is she Alice)’ or ‘她是谁 (Who is she)’. In each of these three sentences, the basic structure is the same SVO structure.

Second, be aware that word order will be changed to express different meanings.

If you are given three words(characters) as ‘人(human; people)’,’杀(to kill)’,’狼(wolf)’. How many meanings can you make by them? If you follow the basic structure, you can make phrases below:

- 人杀狼 (Humans kill wolves)

- 狼杀人 (Wolves kill humans)

Attention, there are no particles marking subject or object in Chinese, if you change the word order, the meaning will be obviously changed.

And we can also make phrases as:

- 杀人狼 (murderous wolf)

- 杀狼人 (wolf killer)

Here are the cases where ‘的’ is omitted. If we add ‘的’ to the phrases as ‘杀人的狼’ and ‘杀狼的人’, it will be easier to find the modifiers and the central words. If you know well about modern Chinese games, you can even make phrases as:

- 狼人杀/人狼杀 (werewolf game)

The phrases are not very standard but can tell another feature in Chinese grammar: verbs are not verbs all the time, they can work as nouns or adjectives sometimes, and vice versa. Therefore, it is not efficient to understand a Chinese sentence by translating it word by word. A better way is to analyze the sentence structure.

As we have mentioned many times above, keep ‘S. TI(me) LO(cation) VO’ and ‘modifier before noun’ in your mind, you can understand most Chinese sentences and make correct sentences easily.

There is no tense in Chinese

It is easy to tell past, present, and future tense by the form of verbs in English. But it does not work in the Mandarin Chinese language. Regardless of whether it is past, present, or future tense, the form of a verb never changes in Chinese. For example:

- 昨天我在饭店吃饭。(I ate at a restaurant yesterday.)

- 现在我在饭店吃饭。(I am eating at a restaurant now.)

- 明天我在饭店吃饭。(I will eat at the restaurant tomorrow.)

The SVO part is the same in the three sentences above, but the time words can help us tell the difference in tenses.

If you want to refute with ‘了(le)”着(zhe)’ to prove that there are particles that can mark tense in Chinese, here comes some new mindset.

First, ‘le’ does NOT mean the past

The main use of ‘了’ is to indicate completion of some action or change of some state.

For example:

- 明天你吃了饭再给我打电话。(Please call me tomorrow after you finish your meal.)

- 刚才天气很好,现在下雨了。(It was sunny, but it’s raining now.)

We use ‘了’ in both of the sentences above, but neither of the events is in the past. The first ‘了’ indicates completion of ‘吃饭’, and the second ‘了’ indicates a change of ‘天气’. Because ‘了’ never means the past, you have to know there are many occasions where you can not use ‘了’ even though the events happened in the past.

If you want to say you did something a lot, you cannot use ‘了’.

For example:

- 小时候,我每天跑步。(I ran every day when I was young.)

- 两年前,我经常喝茶。(I often drank tea two years ago.)

If the verb does not show a visible action, you cannot use ‘了’.

For example:

- 我以前喜欢他。(I liked him before.)

- 我过去是老师。(I was a teacher.)

- 我刚才在洗手间。(I was in the bathroom.)

If you are using adjectives, you cannot use ‘了’ after them.

For example:

- 我以前很瘦,现在很胖。(I was slim, but I am fat now.)

Everyone agrees that it is never easy for foreign learners to use ‘了’ properly, but if you clearly know that ‘了’ is not used for past tense, you can take one step ahead of others.

Second, ‘zhe’ is NOT equivalent to ‘-ing’

If you are going to express some action is in the process, don’t forget that ‘正在/在’ is much more proper than ‘着’. Compared to ‘正在/在 + verb’, ‘verb + 着’ is mostly used for static situations.

Let’s look at the two sentences below:

- 他正在穿衬衫。(He is/was putting on his shirt.)

- 他穿着衬衫。(He is/was in a shirt.)

As you can tell from the translation, ‘正在/在’ is closer to ‘-ing’ in English, while ‘着’ is more used to describe how is the state of a subject.

Ask ‘why’ less and imitate ‘how’ more

Although we are talking about Chinese grammar, some experts still hold the opinion that there is no grammar in the Chinese language, because there are so many exceptions beyond the standard rules written in grammar books. In fact, if you learned more than one language, you would know that all the languages are the same.

Learning some basic knowledge of a foreign language will help you start smoothly. But once you go further, grammatical rules can never answer all the questions you get in your real communication with native speakers. And even if your Chinese teachers can tell you why Chinese people say so all the time, you may find it sometimes doesn’t make any sense if you don’t understand Chinese culture well.

But, ‘sense’ is not so important. The key point of learning a foreign language is ‘to use’. To know how to express yourself is much more important than figuring out why native speakers express themselves in some way, especially at the beginning level.

Therefore, don’t be too aggressive in digging up reasons, especially when you are at the beginning level.

If you are learning some grammar points which are quite different from languages you are proficient in, you can try the following steps to help yourself keep going on:

First, imitate native speakers as much as possible

Listen to native speakers carefully when you are talking to them, and try to note down anything you are confused with. Also, try to find something written for native readers instead of your Chinese learning textbooks, and note down your questions. Then find someone who is patient enough to answer your questions in your notes, such as your Chinese teachers.

Even if you cannot find someone professional enough, you can try to find more examples online with keywords. The key point is to compare all the sentences you find and generalize the contexts.

Imagine some specific context and try to make sentences based on it. Show your sentences to native speakers and ask for feedbacks. You can also summarize the rules of how to use a certain word or a grammar point through their feedbacks.

Second, be tolerant and accept any weird thing

You may not be satisfied with the explanations your teachers gave you. Then think about it: what you are learning is a foreign language and even an alien language. It’s quite normal that it would be different from your common sense.

Learning a foreign language is like making a new friend whose background is completely different from yours. As long as you communicate more, you will get familiar with your new friend and understand deeper.

So, at the very begging: no judge and imitate what you cannot understand by memorizing them.

Third, look back to your confusions often

A good sense of a language is based on enough knowledge of it. Once you have accumulated bigger vocabulary and more grammar points, don’t forget to think about what you were confused with at first. You may surprisingly find yourself understand WHY Chinese people said so and even find yourself naturally express in the same way.

That is to say, ‘understanding’ does not come first all the time. Sometimes, especially for learning something related to cognition, ‘to do’ can also be the first step.

Here are the tips for eliminating some common misunderstandings of learning Chinese grammar. Don’t feel frustrated if you find it difficult to master Chinese grammar. To be honest, Chinese grammar IS difficult, even for experts or researchers. But it can never be an excuse to give up learning Chinese.

Just find some native speakers who are patient enough and practice your Chinese with them. Grammar does not always make sense during real communication, but communication may always make sense for grammar learning.